A GRANDE IDEA

by Charlie Ebbers

Felix Santistevan, Jr., and his five-year-old son Jesus were driving across their family’s ranch, hauling water and checking cattle, when they crested a hill to find a whole herd of elk spread out around them.

“Jesus was sleeping. I shook him, but he didn’t want to wake up,”says Felix. “I stopped the truck and said, ‘Wake up. The elk are here!’”

This was in the late 1980s on land Felix’s father homesteaded north of Taos, New Mexico. Neither one of them ever forgot the sight of those elk so close.

“The herd was all around the truck. We just sat and watched them for a half hour. I remember us pointing at the different animals and saying, ‘Look at that one with the big horns,’ or ‘Look at that baby,’” recounted Felix. “My son, he was 37 years old when he passed, and he remembered those elk until the day he died.”

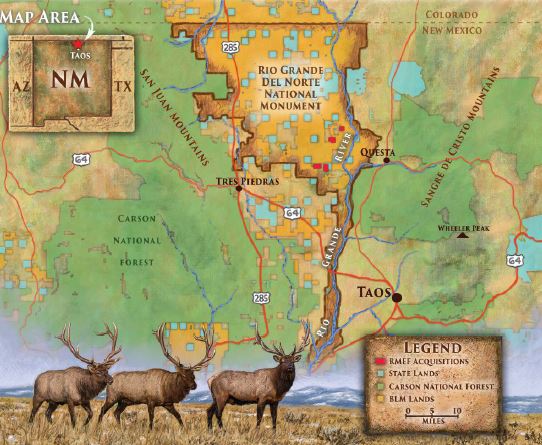

The Santistevan homestead lies in the northern half of Rio Grande del Norte National Monument on the Taos Plateau Volcanic Field, just west of the Rio Grande Gorge. The timbered parcel climbs up a flank of Cerro Montoso, one of several isolated volcanic cones that protrude from the sagebrush and native grassland near the Colorado border at the southern tip of the San Luis Valley. It provides prime winter range for the huge elk herds that roll down onto the plateau when snows pile deep in the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan Mountains.

President Calvin Coolidge signed the original deed for their property back in 1927, granting José Felix Santistevan 649 acres, almost exactly one square mile. According to the Homestead Act of 1862, José had to be a citizen (which he was) and agree to work and upgrade the property for at least five years. Under that act, the federal government dispensed more than 270 million acres to private individuals to settle and cultivate the West. That’s 12 million more acres than what the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) currently

José had to live on the property for at least a year. He built a small cabin by milling timber from the land and flat-notching the boards together. There he and his wife Rafaelita lived, and the cabin was still in use when Felix was born.

nearly 100 years ago on the Taos Plateau.

Felix Jr., now 78, and his mother Rafaelita, 102, sold 324 acres to RMEF in 2019. Once the funding clears for the BLM to purchase it, this land will be added to the surrounding national monument. That will likely happen this fall. (Rafaelita’s other son, Michael, still owns the remaining 325 acres.)

“We provided the bridge funding with money RMEF had set aside for land protection to purchase the property,” says Ryan Chapin, RMEF lands operations manager, who worked closely with the Santistevans. “Then we will be reimbursed by the BLM through the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF).”

This is just one more example of why and how that fund—which uses money paid by oil and gas companies to lease offshore drilling sites to pay to conserve other resources—is so crucial for protecting vital habitat and opening it to the public. Last year the House and Senate voted by overwhelming bipartisan majorities to permanently reauthorize LWCF, but stopped short of guaranteeing that it will be fully funded at the $900 million per year level originally set forth when Congress passed it in 1965. President Trump’s 2021 budget proposed to put just $14.7 million, less than 2 percent of that fund, toward conservation.

So far, LWCF funds have helped RMEF forever protect and open to the public more than 60 properties in 12 states spanning over 165,000 acres of North America’s finest elk habitat—projects like this one on Taos Plateau.

“I realized early on that we had to be very involved in helping Felix and Rafaelita get this one to the finish line,” Chapin says. “The cool thing with the Taos Plateau is that we’re also working to acquire three other nearby parcels, conserving an additional 1,040 acres of great elk country and public access within the monument.”

“It’s beautiful, lots of trees, mostly piñon with a lot of cedar and some pine,” says Felix. After taking ownership almost a century ago, José and his brother, Cruz, brought in livestock and worked to improve the property. Water lies deep underground, about the depth of the gorge that rifts the plateau, so they yoked a team of horses to dig small ponds to catch and hold water from rain and snow for the sheep they ranged across the plateau. They would also haul water from town for the family to use at the homestead.

The challenges were significant. The Rio Grande Gorge plunges steeply more than 300 feet down to that famous river, cutting a deep cleft between them and town. To get water, supplies or medicine, they had to use horse-drawn wagons to cross the plains. When snows melted or rains came hard, mud was so thick they couldn’t travel at all. The Taos Plateau lies roughly 7,000 feet above sea level, with fickle weather that sweeps in quickly from the west before piling up against the wall of the Sangre de Cristo Range. Harsh winters give way to blistering summers, with almost incessant wind year-round. The family moved their band of 1,000 sheep with the seasons, following the best forage. In so doing they shepherded their flock across a broad swath of northern New Mexico, subsisting as much as possible off their surroundings as they went.

“My mom made piñon-based meals from the land,” says Felix. He loved roasted piñon nuts mixed with mutton, venison or elk meat.

The Santistevan family is one of many who homesteaded the area. RMEF is currently working with the BLM and willing landowners to conserve old homestead inholdings within the monument for wildlife habitat, public access and recreation. Despite the pejorative view of monuments in some circles, the citizens of this area pushed for decades to get federal designation. Created in 2013, the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument is just shy of a quarter-million acres and specifically guarantees that hunting and grazing will continue in perpetuity there.

Felix wanted to see their property become part of the monument, but needed RMEF’s help to do it. Due to his mother’s advanced age and his own health challenges, they needed to act quickly.

In the 1970s, the BLM reviewed the Taos Plateau for potential designation as wilderness. In public scoping meetings about the wilderness proposal in 1980, though, most locals didn’t think that designation fit. It would be 33 more years until a monument crafted by and for the people would be created.

Local politicians, Taos Pueblo leaders, miners, ranchers, hunters, anglers, guides and regional businesses met with New Mexico’s congressional delegation to craft a land management plan to protect the area they loved while also allowing them to sustain their livelihoods and traditions.

A Wild Heritage

Taos Plateau is rich in beauty and wildlife. Hot springs, some detailed in guidebooks and online, some still held secret among locals, fringe the Rio Grande. A federally designated Wild and Scenic River since 1968, the 70-mile-long gorge offers seclusion and outstanding fishing for those willing to hike in and out of the often nearly sheer gorge. It also offers everything from maximum intensity Class V whitewater in Taos Box to family-friendly floats. Peregrine falcons and golden eagles raise their chicks on its walls, and endangered southwestern willow flycatchers nest in the river bottom.

Thousands of elk pour onto the plateau every winter from the Sangre de Cristos to the east and San Juans to the west. Wheeler Peak, the tallest mountain in New Mexico, outlines the sunrise. Bighorn sheep graze high in the mountains. Down in the canyon, the Taos Pueblo tribe reintroduced 48 bighorns in 2006. That herd has since grown to more than 300. Mule deer thump through the sage and disappear into the breaks in a landscape that turns out to be not as flat as it first appears. A unique high-elevation pronghorn herd summers above 10,000 feet, then flows across the plains, seemingly impervious to the axle-deep, chilled mud.

“A large elk herd of up to 27,000 elk inhabits the region encompassing the northern Sangre de Cristos,” says Nicole Tatman, New Mexico Game and Fish (NMGF) big game program manager. According to NMGF, hunters spend more than $31 million each year in Taos and Rio Arriba counties alone. She says some elk spend all year on the Taos Plateau, while thousands more migrate in when snow stacks up in the higher elevations.

but now takes care of his 102-year-old

mother Rafaelita (right).

Last year NMGF selected this area as one of just four in the state where they aim to focus resources to sustain key big game migrations. That includes conducting research to better understand the magnitude, timing and stopover areas of these migratory herds of elk, mule deer and pronghorns.

“The Rio Grande del Norte National Monument is a large landscape that is mostly intact for winter range,” Tatman says. “ area fulfills a key part of the herd’s needs, and the Santistevan homestead is part of that. It’s hard to get to and for most of the year, inaccessible.”

Felix remembers a day when he was a boy when he had to walk 10 miles to Tres Piedras, an unincorporated community, to get a replacement tire for their 1941 Dodge step-side truck. It took him the better part of the day to make it back to his dad and uncle with a new tire. While both tires and the major roads of the area have since improved, getting stranded in the monument is still far from rare.

Felix had a bit of advice on that subject.

“Even if you have a big four-wheel drive, if it rains, get out.”

Periodic bouts of mud notwithstanding, people have been hunting and living on this landscape for upwards of 8,000 years. Their art decorates rock walls and their stone tools stud the landscape.

Archeologists in the 1940s found basalt and obsidian chipped for stone tools that were dated to 6000 B.C. They mapped ancient campsites large and small, basalt outcrops that had been quarried for tools, and lookouts on top of exposed mesas. Today, the majority of the monument remains devoid of modern human developments.

The Pueblo Indians, however, settled the area in the late 13th and early 14th century and have lived continuously in the Taos Pueblo to this day. The construction of ancient pueblos on the plateau is similar to Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde, both of which have become national parks. The land managers and politicians sought counsel from the Pueblo leaders on what they’d want a monument to look like.

In 2012, a year before the monument was officially designated, then Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar hosted a town hall meeting in Taos. Every seat was filled and people lined the walls. Spanish land grant heirs, Pueblo leaders, acequia associations, hunters, anglers, guides, ranchers, miners and energy producers filled the room. Salazar presented the boundaries and regulations of the proposed monument. He asked the room to raise their hands if they supported the proposal. It was reported that every hand went up.

One look at the enabling paperwork and it’s apparent why. The BLM and the Interior Department are charged with managing the monument with the public interest at the forefront. The designation allowed existing mines to continue operation, but halted new mines from being developed. It allowed for utility lines to remain in place, and neither enlarged nor diminished the rights of any of the local tribes. Local uses like livestock grazing, firewood collecting and piñon harvesting are still permitted for all citizens. Hunting, fishing, camping and hiking are all allowed and encouraged, and the BLM is tasked with ensuring those activities continue.

Sheep to Cattle

José turned the property over to Felix and his brother in the 1970s. Felix ran white-faced Herefords that always put on weight out at the old homestead. The family had moved the original cabin to their place near town, and Felix hauled water in 55-gallon drums out to the cattle three times a week. In the mid- 1970s, they dug a well. The first drill went all the way down and hit water, but “we hit a cave and lost the driller’s stamp,” recalls Felix. “So we went about

Felix brought in a propane generator pump and two stock tanks. His property was now mostly self-sufficient. The native grasses were great forage for his cattle, and he nally had water on site. It was an anchor for his herds and his family. They collected piñon nuts, raised cattle and hunted there until the early 2000s when a major drought stunted vegetation, so he pulled the cattle off and quit grazing the parcel. Someone later stole the two water tanks, and without the homestead, the property went back to looking like it did when his father first came to the area.

And so their land remained for over a decade, until Felix approached the BLM about selling his property. They reached out to RMEF. It’s a win-win for some of New Mexico’s finest elk country and the Santistevans as well. Felix is using the money from the sale to pay for healthcare for Rafaelita, and to start a college fund for Jesus’s two children. RMEF is happy to create those kinds of side benefits while ensuring this slice of vital elk country will never be developed into anything other than prime wildlife habitat.

Charlie Ebbers is a journalist interested in public lands and wildlife. He’s also a seasonal trail crew leader for the National Park Service, who loves to hunt with a hand-me-down rifle.