What do elk teeth and tree stumps have in common? Both can be aged by counting their rings.

Here’s how it works and why it matters.

by Tana Wilson

Editor’s Note: This is the first edition of a 3-part series about scientific aging using elk and other wildlife teeth— a service now offered to hunters through Matson’s Laboratory.

With a skyline of mountains instead of skyscrapers, Manhattan, Montana (population 1,550) bears little resemblance to the East Coast metropolis by the same name.

But when it comes to animal teeth, it’s a world capital.

More than 100,000 specimens from scores of species arrive there by mail each year to Matson’s Laboratory, a privately-owned wildlife lab that is a world leader in aging animal teeth.

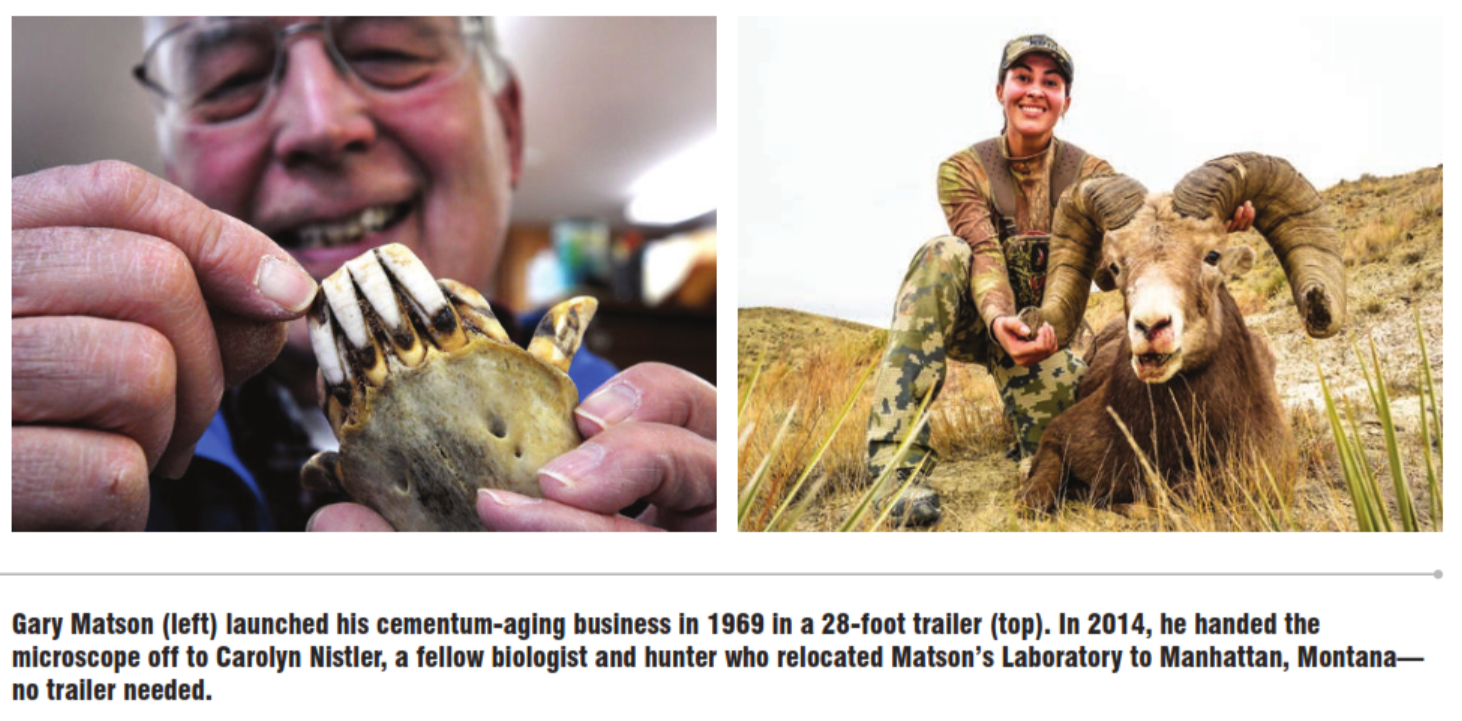

Matson’s has been processing wildlife teeth for almost half a century. Gary Matson launched it in 1969 in even tinier Milltown, Montana, 180 miles to the west.

“When we first started, we converted a 28-foot mobile home into a lab,” Matson says. “It was really quite pathetic. The roof leaked…everything leaked.”

Matson was busy getting his master’s in zoology at the University of Montana when a friend and fellow student named Merlin Shoesmith suggested he try cementum analysis using elk teeth.

Back then it was relatively new tech used mainly for aging marine mammals. But Shoesmith was working in Yellowstone National Park studying elk on Specimen Ridge.

He began shipping Matson batches of elk teeth he’d collected from winterkills in the park. Cementum analysis immediately showed promise for aging elk. Matson soon tried it for aging black bears as well and found in some cases it revealed secrets beyond age.

Like Tree Rings in a Tooth

All mammals deposit annual layers of protein within their cementum—the calcified or mineralized tissue layer covering the root of the tooth located in the bony socket below the gum line.

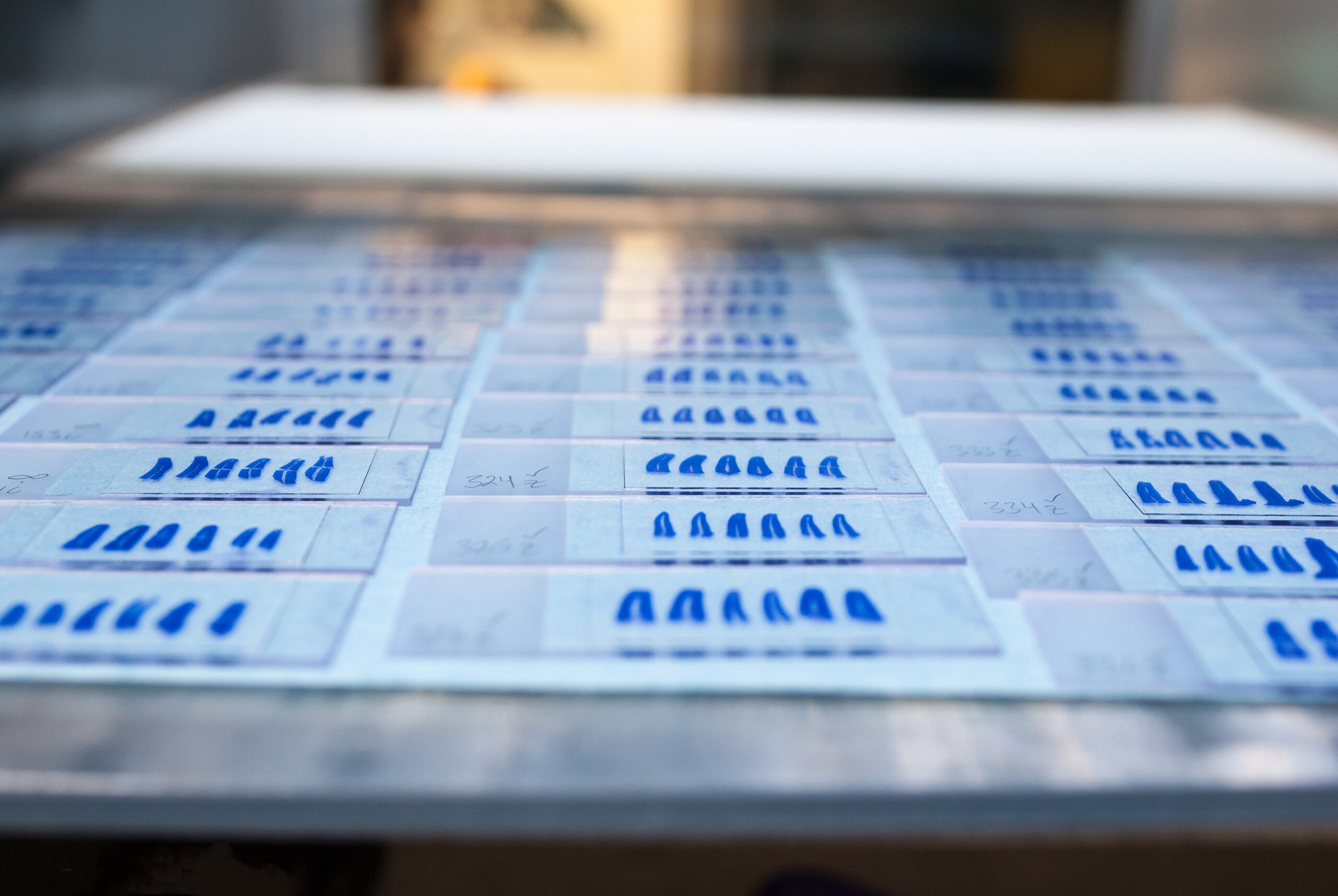

Running an incisor through a blend of hydrochloric acid and formalin softens it into the consistency of a rubber eraser. That allowed Matson to use a precision microtome—a six-inch-long, razor- sharp blade—to shave a cross-section off the tooth, a slice so thin it’s transparent. Put on a microscope slide and stained, this reveals the growth rings.

Matson started teaching himself how to count them, which is not often easy. But as he trained his eye and tested himself again teeth of a known age, his accuracy steadily improved.

He soon said goodbye to his trailer and built a lab in Milltown, just outside of Missoula, where he processed more than 2 million teeth over 40 years. Matson steadily refined the process to be more accurate and grew the business with a steady flow of teeth from state wildlife agencies.

In 2014, Matson retired and handed the microscope off to Carolyn Nistler, a fellow biologist from the Bozeman area. She purchased the lab and relocated it to Manhattan.

“It has been really a good fit for me to mold the biology with the business side of things,” she says.

Matson’s Lab has aged teeth from all 50 states and all seven continents. The majority of business comes from the United States and Canada, along with some European countries, especially Sweden and Finland.

Aging a World Record Bull

While wildlife biologists supply the vast majority of the teeth, around five percent of those aged annually are sent in by hunters, including the new typical archery world record bull killed in Montana in September 2016.

That bull aged in at just 6 years old, far younger than anyone expected. As a rule, mature bulls produce their largest set of antlers between nine and 12 years of age, so to find a record-sized bull this young is rare indeed.

Nistler was excited to age the record bull last June and found that the tooth samples were as absolute as aging teeth can be when she examined the bull’s primary incisor under the microscope.

“Sometimes elk are really tricky and have multiple components, but we lucked out. This one was really clear.”

To learn more about cementum and how hunters can send in teeth from game to get them aged, visit www.matsonslab.com