By Chris Madson (originally published in the January-February 2025 issue of Bugle magazine)

In southeastern Wyoming, an innovative agreement years in the making protects elk habitat and expands public hunting access.

In the modern West, conservation can get complicated.

The land itself is divided among a mind-bending collection of federal and state managers with startlingly different missions, along with a galaxy of private landowners with widely differing views on how they want to use their property and what they want it to provide. Many of America’s most significant big game herds—bighorn sheep, moose, elk, mule deer, pronghorn—migrate across this crazy quilt of ownership and divergent objectives. They were here before the fences, and they go where they know there’s forage and shelter without any concern for human priorities. Complicated. These days, the conservation success stories are just as complex, a combination of the right place, the right people…and, often, a mind-bending span of time.

The Mule Creek project is one of those stories.

The Place

Mule Creek starts on the western slope of what the old trappers called the Black Hills, a spine of high country that separates the sagebrush grasslands of Shirley Basin from the vast expanse of the Great Plains to the east. For the mountain men coming up the Platte, it was the first range of the Rockies, a rampart blanketed with native grasses and pines, seamed with canyons and watered by snow-fed creeks and springs.

The hills have always been good game country. In 1846, the Boston dude, Francis Parkman, rode west out of Fort Laramie to spend the summer with a band of Lakota hunting in the Black Hills and out into Shirley Basin, which he later chronicled in his book, The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life.

On his way up the Laramie River, his party watched as “a herd of some two hundred elk came out upon the meadow, their antlers clattering as they walked forward in a dense throng.” After a summer among the bison and antelope of the Shirley Basin, he was traveling back through the Black Hills when “a long file of elk came out at full speed and entered an opening in the mountain.” A second later, one of his companions yelled, “’Come on! Come on! Do you see that band of big-horn up yonder? If there’s one of them, there’s a hundred!’”

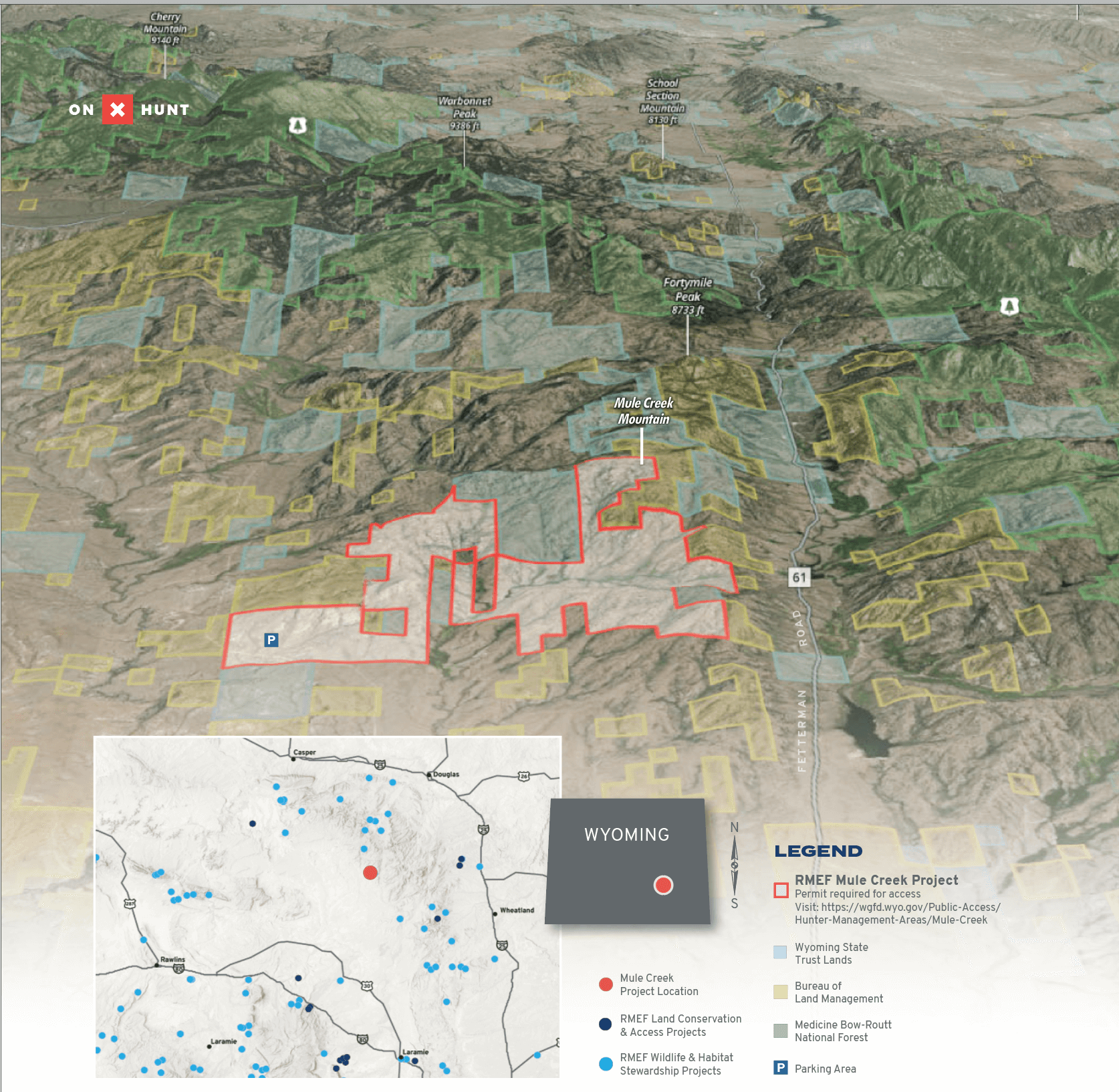

In the decades that followed Parkman’s visit, the tide of settlement and civilization from the East parted around the Black Hills, known today as the Laramie Range, and left the region almost untouched. A modern traveler aiming to visit the Mule Creek country is well advised to come between May and October; during the winter, the scanty roads are closed by blizzards about as often as they’re passable. When it’s open, the dirt-and-gravel Palmer Canyon Road winds up through the mountains from the town of Wheatland, 30 miles as the raven flies, to Mule Creek. Or there’s the Old Fetterman Road, another gravel track that leaves the pavement just north of the metropolis of Rock River and strikes 30 miles north across the high prairie to Mule Creek, then runs another 50 miles to the next highway. Mule Creek isn’t the exact middle of nowhere, but you can see it from there.

Which is at least part of the reason elk have done so well there. For Ryan Amundson, terrestrial habitat biologist with Wyoming Game and Fish, the Mule Creek country is something special.

“I’ve called that area southeast Wyoming’s ‘little Yellowstone,’” he says. “It has all the necessary components for elk, and the juxtaposition of how things are arranged is really good. I’ve had some amazing times up there. Horseback, surveying some project work we’ve just completed, I’ve had to pause for an hour, just to listen to elk sing—incredible, jaw-dropping stuff, hundreds and hundreds of elk sometimes, in the late fall, and elk bugling in September. The place has just got tons of wildlife.”

Wyoming Game and Fish sets population objectives for each big game herd in the state. The goal for the elk herd around Mule Creek is 4,000 to 6,000 animals. In 2023, biologists estimated it held about 12,000. Those numbers would be music to a hunter’s ears…except that much of the best elk range in the region is privately owned and can be difficult to access. For many ranchers in the area, the current elk population is just too much of a good thing.  The People

The People

In 1996, Colorado businessmen Ken Matzner and Sam Shoultz bought the 6,660-acre Mule Creek Ranch primarily for elk hunting, and right from the start they took a keen interest in the health of its range. “The whole goal is to create better habitat,” Shoultz says, “create better habitat for cattle, create better habitat for the wildlife. We try to leave plenty of feed for the elk. It’s always been a goal to treat the land so that it will continue to support you. If you abuse it, it’ll take years to come back.”

With that goal in mind, the partners contacted Amundson to help them improve the range. Working with the owners and managers there, Game and Fish, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, the Bureau of Land Management and other conservation interests have improved the habitat with a variety of techniques—rejuvenating aspen stands, thinning conifers, controlling juniper and cheatgrass, building wildlife-friendly fences, unclogging spring seeps and fencing them so they continue to run.

The day-to-day management of cattle on the ranch has mostly been in the hands of one of the area’s first families. In 1877, Sgt. Mike Henry left the Army at Fort Laramie and started raising horses along the Bozeman Trail. Five generations later, Garrett Henry carries on that tradition, raising quarter horses for ranch work and rodeo along with a thriving cattle herd. When Shoultz and Matzner bought Mule Creek, they leased the grazing to Garrett’s dad and, later, to him.

“This place—there’s a lot of reasons I love it,” Garrett says. “I spent a ton of time up here with my dad and my brother.”

The three were at Mule Creek when his dad felt the first symptoms of the brain cancer that eventually claimed his life. “He was just not feeling well and went off the mountain,” Garrett remembers. “This was the last place we were—I guess you want to call it—normal together. It was just always a special spot. Meeting Sam’s goal of conserving it forever, not allowing it to be chopped up into many 40-acre parcels, was huge.”

Another key player in the story is Leah Burgess, RMEF senior conservation program manager in Laramie. After 15 years on Mule Creek, Shoultz and Matzner knew they’d put together something exceptional. They wanted to keep it that way, so, in 2013 they asked Burgess for help. Drawing on her extensive experience working with landowners to protect the wild quality of a privately held property, Burgess got to work.

Time

In 2013, Shoultz and Matzner expressed interest in selling Mule Creek to RMEF, but a straightforward purchase was more than the foundation’s budget could handle. One alternative was to place the land in a voluntary conservation agreement (VCA, also known as a conservation easement) to protect the ranch and its habitat, then find a buyer. The other approach was a land swap. The Bureau of Land Management could trade land it controlled in exchange for the Mule Creek Ranch, bringing the ranch under federal management.

One option depended on finding the right buyer; the other involved negotiations with a federal agency. Neither one was likely to be a quick fix. In the meantime, RMEF and Game and Fish negotiated a lease with the owners in 2015 that opened the ranch to public hunting—a stop-gap measure while the principals worked on something more permanent.

On March 28, 2016, Ken Matzner died after a long struggle with cancer. Burgess speaks for the rest of the professional conservationists involved when she says, “We knew we had a responsibility to ensure Ken’s dreams of conserving Mule Creek Ranch became a reality.”

Amundson agrees.

“Ken and Sam—I call them visionaries,” he says. “They wanted to make sure that place was conserved in perpetuity, but they also wanted to share it with other people. I thought that was really big of them.”

In 2019, RMEF secured the option to purchase the ranch if all other options failed.

Negotiations over the BLM land exchange dragged on, and as COVID-19 struck, it complicated the process even further. By 2022, it was clear to Burgess and partners at The Conservation Fund that the exchange wasn’t likely to happen, so RMEF exercised the option it held on the property to buy the 6,660 acres of Mule Creek.

“In the end,” Burgess says, “I think that was for the best. It really enabled us to get a better feel for the ranch, the management, the grazing system, the neighbors and the Henry family who had had a long history of grazing that ranch, starting with Garrett’s dad. It’s a neighborhood with a lot of history and families. They worried it would become a roaded free-for-all if it became public, and then you blow the elk out anyway.”

Even before RMEF’s purchase of the ranch, the Henry family had demonstrated their commitment to the conservation goals at Mule Creek, so RMEF leased the grazing rights to them while the permanent conservation and ownership solution developed.

But RMEF isn’t in the cattle business, and wanted to put Mule Creek in the hands of people who would take care of it. Garrett Henry had long expressed an interest in owning some of the range his family’s cattle grazed for generations, and Game and Fish saw potential for a new wildlife habitat management area on at least some of the property. More talks ensued.

The resulting real estate transactions closed in May 2024. Game and Fish took title to 2,660 acres on the west side of the ranch, now a Wildlife Habitat Management Area. Garrett Henry and the 88 Ranch took title to 4,000 acres on the east side. That parcel is protected by a voluntary conservation agreement (VCA) with permanent public elk hunting access guaranteed. Access to both is issued by a Game and Fish draw.

RMEF covered the many administrative costs and reduced the price of the VCA as part of its contribution to the outcome. Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust and Knobloch Family Foundation also generously contributed to the VCA. Non-motorized public hunting will be allowed on the entire parcel. Combined with the state and federally owned land surrounding the ranch, the area covered by the Mule Creek Wildlife Habitat Management Area, the VCA, and the public access agreement will protect 6,660 acres—and connects to more than 34,000 acres of prime elk habitat.

Garrett Henry is enthusiastic about the future at Mule Creek. “I love hunting. It’s not just that I ranch. I want to take care of it from a hunter’s perspective, too, and have good wildlife and hunting.” He’s also pleased to continue the access hunters have now enjoyed for several seasons. “I don’t know how many people I’ve ran into over the years—you mention Mule Creek and they say, ‘Oh, yeah, I killed an elk up there four years ago.’”

Game & Fish’s Ryan Amundson is glad to have Garrett as a long-term partner on the place.

“I’m excited to have a progressive producer on site,” he says. “I think he’s somebody who’s really willing to work with us, and we’re really willing to work with him. This is a great example of how we might keep young people in ag. By the time they put a conservation easement that included a public access component on that piece, it made it affordable for a young rancher like Garrett Henry to purchase.”

“In the end, it was a great outcome,” Burgess says, looking back over 11 years of work with the committed group of rancher-conservationists, agency and NGO personnel. “This project was touched by resource and real estate staff from state and federal agencies, private conservation organizations and extraordinary ranching partners. It was a recipe for success with an outcome we can all feel good about.”

Amundson says RMEF and Burgess in particular were critical to getting this project across the rough patches.

“RMEF is one of our top partners, always there at the table and one we can rely on to come through whether it’s a grant for habitat work or a large land conservation effort like Mule Creek. RMEF also has tenacious staff like Leah Burgess who don’t get frustrated when these projects take a detour as Mule Creek did. She always remained its biggest champion, and as it took those detours, she didn’t falter. She stayed positive, and that positive energy helped keep everyone engaged so we didn’t lose traction or fall off course. We stayed with it, and we trusted her to get us to the finish line—and that’s what happened.”  The scope of the Mule Creek project is impressive enough, but as Amundson points out, there’s hope that it can be a template for a broader experiment in conservation. Elk in the Laramie Range are held in trust for the public, but much of the burden of providing for them falls on a handful of ranchers in the area. The public owes those ranchers some help in bearing that burden.

The scope of the Mule Creek project is impressive enough, but as Amundson points out, there’s hope that it can be a template for a broader experiment in conservation. Elk in the Laramie Range are held in trust for the public, but much of the burden of providing for them falls on a handful of ranchers in the area. The public owes those ranchers some help in bearing that burden.

Since the last acre of frontier was settled, wildlife management in the West has depended on a partnership between the people on the land and the hunting public. With enough access, hunters can trim the elk herd in the Laramie Range down to state population objectives. And they can help fund the habitat management, cost-sharing, conservation strategies and outright land purchases needed to keep elk on the modern landscape. That’s what happened at Mule Creek. It’s a heartening example of the commitment the American hunter has long shared with the American landholder.

Long may it continue.

When he’s not hunting, Chris Madson writes on wildlife conservation and the environment from his home in Cheyenne, Wyoming.