Below is a submission by Craig Springer who works with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program

It seems odd to say this, but Ohioan Joseph List may have lived much of his adult life without ever seeing a white-tailed deer. This first-generation American, born in 1860, experienced his spring of life at the dawn of the Civil War. This son of German immigrants was Everyman from Anytown, USA—and he was a hunter.

He called Sardinia home, a small town a short distance from the Ohio River, nestled amid the gentle hummocks and hills left behind by retreating mile-thick glaciers many millennia ago. It was then as it is now, a small town servicing agriculture.

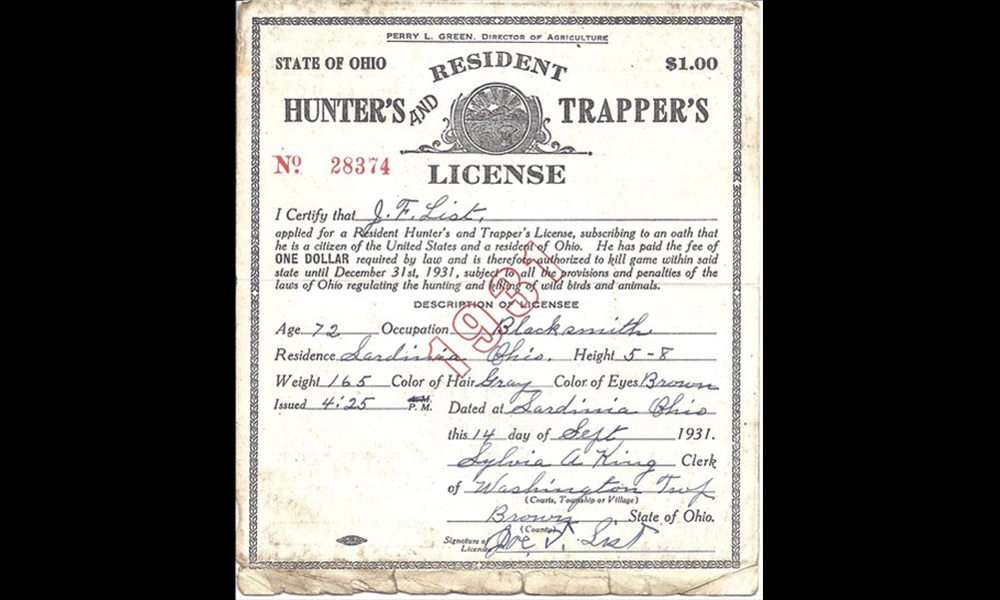

List made a living as a blacksmith. That is what he noted on his 1931 Ohio Department of Agriculture hunter’s and trapper’s license (see image above). It cost him one dollar for the privilege to harvest game and furbearer pelts. He was 72 years old when he laid his signature down. The faded ink, its tattered and feathered edges mark the passage of nine decades since he and the township clerk put pen to the linen paper. The crease is likely evidence that he folded it to display in an envelope worn on the back of a hunting coat so that conservation officers could easily check it in the field.

The hunting regulations that List carried in his coat speak to prevailing conditions that would soon lead to landmark conservation legislation, the passage of the Pittman-Robertson Act, six years away. Its soiled pages of heavy, durable card stock show he thumbed it a time or two, but two lines of text stand out.

Deer: Protected

Ruffed grouse: Protected.

One species in notably absent—wild turkey. There is no mention of the bird in the proclamation. Wild turkey no longer existed in Ohio.

By the time of List’s birth, white-tailed deer had already been in great decline over much of its range. Unregulated subsistence and market harvest coupled with habitat loss eventually made white-tailed deer a rarity. The Civil War had an effect on wildlife where List lived.

The hilly Appalachian Piedmont of southern Ohio proved important in saving the Union. The area produced vast amounts of pig iron for ship hulls and bayonets, cannons and kettles. The place names that dot the map, Ironton, Buckeye Furnace, Scioto Furnace, and Vesuvius Furnace tell of a precinct in military and conservation history. The literal furnaces were conical limestone edifices that required two things: iron ore—and lots of wood. The smelters converted red maple, white oak, and yellow pine into molten dusky metal leaving a denuded forest in ever expanding concentric rings. The iron industry continued into the late 19th century. By 1900, very little of Ohio’s mosaic woodlands remained. Statewide, the deer were gone. A vestige of ruffed grouse remained.

The decline in wildlife experienced in Ohio is but an example of the conditions that prevailed over much of the county when List went afield in 1931. Pronghorn no longer skittered over the short-grass prairies of the West. Wild turkey were rare. Elk in the western United States were nearly a thing of the past by 1910, and had long been extirpated in the East.

While List was the Everyman, fellow Ohioan Carl Shoemaker was a man of uncommon abilities—and he too was a hunter. Shoemaker was born at the other end of Ohio opposite List in Napoleon, so named for Emperor Bonaparte, as its early inhabitants were of French extraction. Shoemaker’s mother in fact emigrated from France. Shoemaker was born in 1882 and came of age close to the Maumee River on its downhill course toward Lake Erie.

Shoemaker attended Ohio State University, earning his terminal degree in law in 1907. He hung out a shingle in Columbus, but that proved temporary. He moved west in 1912 to remake himself; he landed in Roseburg, Oregon, where he published the Evening News. His interest in politics and conservation converged with an appointment as State Game Warden and head of the Oregon State Fish and Game Commission in 1915. He held the position for 13 years. He wended his way back east and in 1930 signed on as an investigator with the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Conservation and Wildlife Resources and remained employed by the committee until 1947.

In the spring of 1937, it was Shoemaker who crafted the legislation to impose an excise tax on sporting arms and ammunition manufacturers as a means to pay for conservation. He wrote what would become the Pittman-Robertson Act that profoundly moved wildlife conservation. Shoemaker met with leaders in the firearms industry and they were agreeable. Commerce would fund conservation—and it still does. Firearms, ammunition and archery manufacturers pay a 10- to 11-percent excise tax on select goods.

Shoemaker shepherded the legislation to key Senate staff as well as the House. Rules in the House of Representatives required the bill to go through the Agriculture Committee, as the USDA’s Bureau of Biological Survey would have purview of the eventual law. It fell to Representative Scott Lucas of Illinois to move the bill along. But he stalled. Then a curious thing happened. Shoemaker urged women’s groups and garden clubs of Illinois to cajole the representative in reporting the bill out of committee. And it worked. Shoemaker later wrote of the encounter with Lucas near his office: “He threw up his hand and exclaimed, ‘For God’s sake, Carl, take the women off my back and I’ll report the bill at once.”

The Pittman-Robertson Act became law in September 1937. Within a year, 43 of 48 states passed laws protecting hunting license sales from use other than running the state fish and game agencies. The new Division of Federal Aid would fund three types of projects with excise taxes: land acquisition, habitat improvement and scientific research directed at wildlife restoration, all performed by the state fish and game agencies.

In 1938, the first Pittman-Robertson project was underway; a waterfowl habitat improvement project paid for by $7,500 of excise taxes with $2,500 matching monies by the Utah Department of Fish and Game.

In 1939, the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, created in 1871, absorbed the Bureau of Biological Survey. The two combined became the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the Department of the Interior. In addition, that year, the state fish and game agencies across the county received their first wildlife restoration grant money. Ohio landed $39,017, which likely paid for long-term ruffed grouse research in southeast Ohio that commenced that year, as well as white-tailed deer research.

In 1943, Ohio held its first deer season since 1900. The season lasted three days in three counties adjacent to where List still lived. In 1950, 40 of Ohio’s 88 counties hosted a three-day-long season where hunters harvested approximately 4,000 deer. In August of that year, Congress passed the Dingell-Johnson Act, modelled largely on the success of Pittman-Robertson, for the benefit of fisheries management, research, and angler and boater access.

Joseph List left his earthly domain nearly two months later. He died in late September 1950, having outlived eight of his 13 children and witnessed a good many events in his 90 years. Today, deer season opens in late-September in the Buckeye State and runs in some fashion to the first week of February. In the 2019-20 season, hunters harvested 184,465 white-tailed deer. The Ohio Division of Wildlife received in 2020, $12.2 million in Pittman-Robertson funds administered through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program.

Autumn is for recalling a confection of past deer camps, old bird dogs, and friends that have passed through our lives. We also remember that our abundant wildlife has not always been so. October is the fulcrum month that heaves summer fully into fall. Carl Shoemaker was a fulcrum of sorts who heaved the Pittman-Robertson Act into law. The resulting industry-state-federal partnership has been a boon to wildlife conservation and people across the country.

(Photo source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)